Imagine if a cardiovascular stent, after propping open a blood vessel and restoring blood flow, could retire gracefully and quietly dissolve into the bloodstream. Imagine if bone plates and screws used to fix fractures could disappear once healing is completeŌĆöeliminating the need for secondary removal surgery. Imagine if tissue-engineered scaffolds could provide precise physical support for cells, actively guiding and accelerating tissue regeneration. These scenarios are not futuristic visionsŌĆöthey represent the revolutionary landscape that biodegradable polyester materials are bringing to modern medical devices.

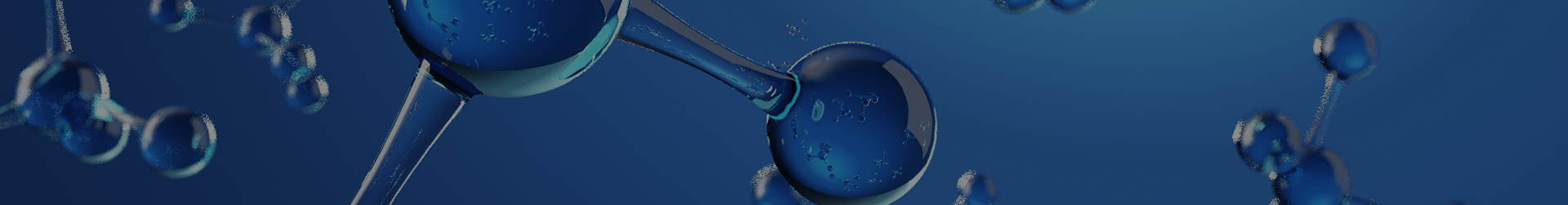

Figure 1. Development of biodegradable polyester materials in medical devices

1. Clinical Pain Points: Why Medical Devices Need to ŌĆ£Retire GracefullyŌĆØ

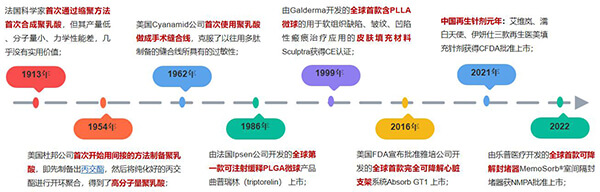

In 2021, approximately 10 million people worldwide died from coronary artery disease (CAD). CAD occurs when the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart become blocked, causing myocardial ischemia and hypoxia. Implantation of cardiovascular stents is the gold standard for treating coronary artery disease. Stents provide mechanical support to vessel walls and significantly improve the quality of coronary revascularization [1].

Figure 2. Sites of coronary artery disease onset

Traditional cardiovascular stents are mainly bare-metal stents and drug-eluting stents, typically made from stainless steel or cobalt-chromium alloys. The mechanical strength of bare-metal stents far exceeds that of the vascular intima, leading to neointimal hyperplasia, in-stent restenosis, and early thrombosis. Drug-eluting stents inhibit neointimal hyperplasia by releasing antiproliferative drugs, but delayed re-endothelialization may cause late stent thrombosis. In addition, the non-degradable nature of metallic stents often results in chronic long-term inflammation.

Figure 3. Abbott Xience L605 cobalt-chromium drug-eluting stent

Bone possesses self-healing and regenerative potential, but severe bone defects cannot be fully repaired through natural healing alone. Clinical strategies to treat such defects include allografts and autografts, inducing a fibrous membrane via the Masquelet technique, and distraction osteogenesis that leverages natural bone healing. However, bone grafts are limited in supply, risk immune rejection, and have poor bioactivity; the Masquelet technique requires two surgeries and has uncertain outcomes; distraction osteogenesis has long treatment cycles, demands high patient compliance, and has severe complications [2].

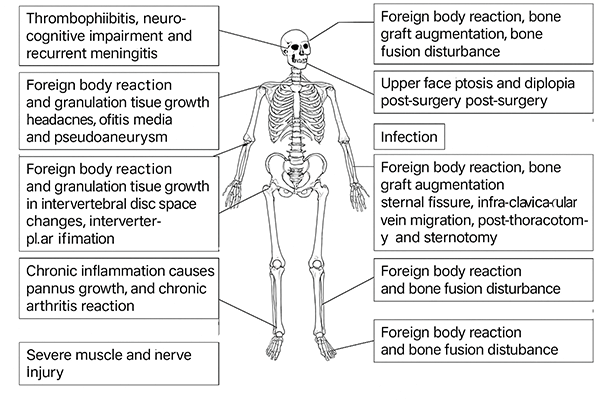

Bone wax is an essential hemostatic material used in orthopedic, neurosurgical, and thoracic surgeries. Conventional bone wax is typically composed of refined beeswax and medical-grade petroleum jelly, supplemented with small amounts of mineral oil or isopropyl palmitate, providing good molding and hemostatic abilities [3].

However, due to the inherent biological inertness and non-degradability of beeswax, bone wax exhibits poor biocompatibility. After implantation, it readily triggers uncontrolled inflammation and foreign-body reactions, increases infection risk at bone defect sites, and impedes bone regeneration [4].

Figure 4. Adverse reactions caused by traditional bone wax after implantation [3]

In the aesthetic medicine field, first- and second-generation facial fillers mainly based on collagen and hyaluronic acid are widely used for facial shaping and tissue repair. However, these traditional materials primarily provide physical filling, with limited ability to stimulate collagen regeneration and tissue repair. The filling effect is often unnatural, short-lived, and difficult to customize for individual needs, hindering advances in precision aesthetic reconstruction.

Figure 5. Effects of hyaluronic acid with different molecular weights on the human body [5]

Overall, although traditional non-degradable medical devices are widely used across cardiovascular interventions, neurosurgery, orthopedics, plastic and maxillofacial surgery, otolaryngology, cosmetic medicine, general surgery, oncology, and regenerative medicine, their non-degradability leads to uncontrollable inflammation and long-term foreign-body responses. This increases patient discomfort, economic burden, and infection risks. Moreover, non-degradable orthopedic fixation devices and sutures often require secondary removal surgery, making it impossible to achieve in-situ tissue regeneration and repair.

2. The Key to Breakthrough: Biodegradable Polyester Materials

These clinical challenges have driven the search for advanced materials. Biodegradable polyester materials, with their unique properties, offer ideal solutions.

Biodegradable polyesters contain ester bonds in their polymer backbone that can be cleaved via chemical, biological, or physical mechanisms under specific conditions, breaking down into small-molecule products that can be metabolized or naturally eliminated by the body. Representative biodegradable polyesters widely used in medical devices include polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and polycaprolactone (PCL).

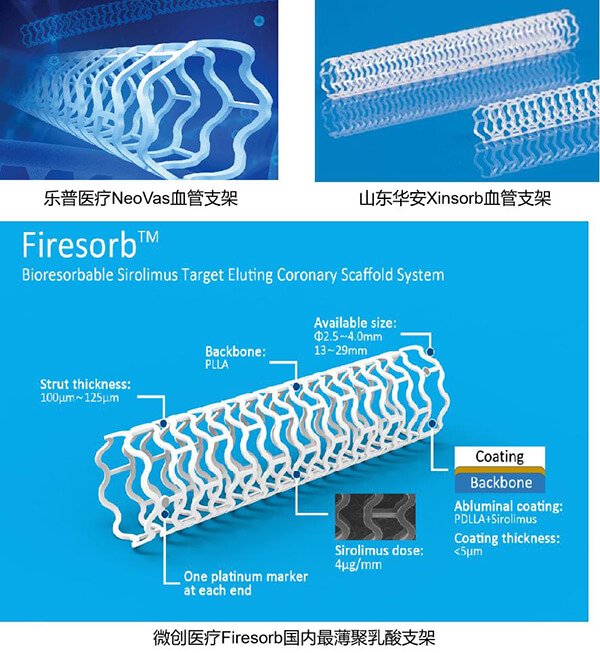

2.1 Biodegradable Cardiovascular Stents

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA)ŌĆōbased cardiovascular stents have been widely used in clinical trials and commercialized. Chinese companies Lepu Medical, Shandong Huaan Bio, and MicroPort have each launched domestic PLLA stents, with racemic PLA coatings loaded with sirolimus. The racemic PLA coating degrades first, slowly releasing sirolimus to prevent restenosis caused by excessive vascular repair. Before vessel remodeling and functional restoration occur, the PLLA stent provides temporary mechanical support to prevent acute elastic recoil. As the stent gradually degrades, vascular contractile function is restored, the risk of late thrombosis is reduced, and chronic long-term inflammation associated with traditional stents is alleviated.

Figure 6. Commercially available biodegradable cardiovascular stents in China

2.2 Biodegradable Orthopedic Repair Devices

Commercial biodegradable bone wax products are relatively simple in composition, typically using biodegradable polyesters, degradable alkoxy copolymers, and polyethylene glycol as the matrix. The U.S. company Hemostasis LLC launched BoneSeal, a biodegradable bone wax composed of 85ŌĆō90% PLA and 10ŌĆō15% hydroxyapatite (HAp). Compared with traditional bone wax, biodegradable bone wax shows higher biocompatibility, stronger osteogenic potential, and does not induce long-term foreign-body reactions or inflammation after degradation [6].

Figure 7. BoneSeal biodegradable bone wax

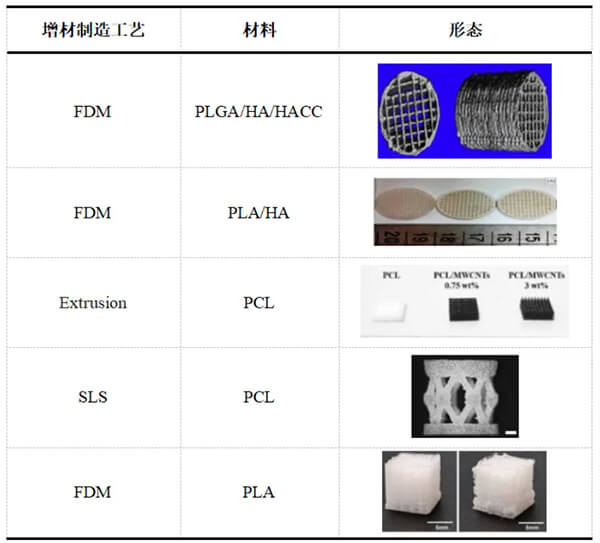

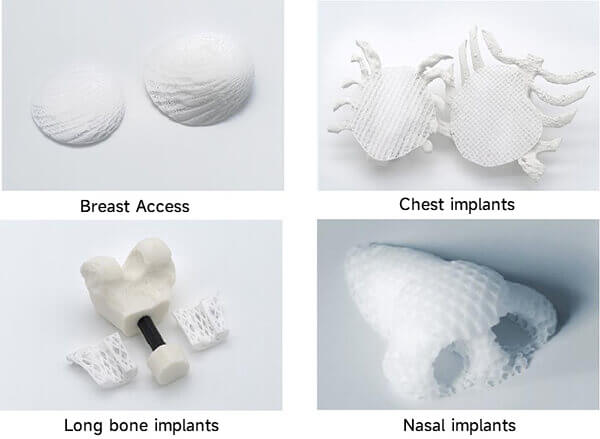

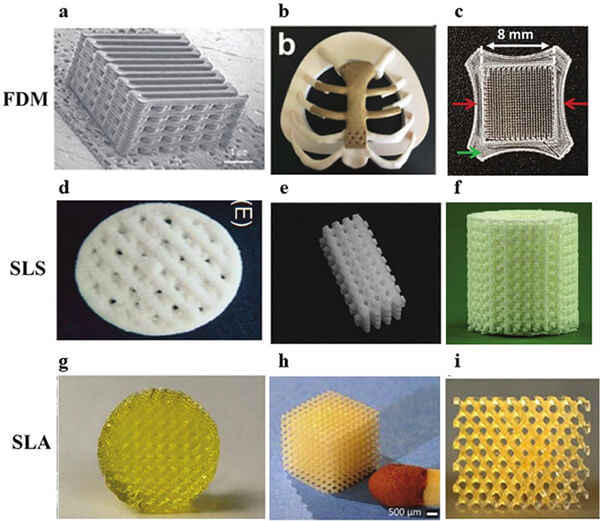

Tissue engineering, combining scaffolds, cells, and bioactive factors, offers a more sustainable strategy for long-term tissue repair and regeneration. Biodegradable polyesters, with excellent biocompatibility, tunable degradation, and appropriate mechanical and physical properties, serve as ideal scaffolds. Meanwhile, 3D printing provides personalized, high-precision fabrication of functional scaffolds that mimic extracellular matrix structures, enabling uniform cell distribution for tissue repair and regeneration [8].

Table 1. 3D-printed biodegradable polyester scaffolds for bone tissue engineering

BellaSeno has already commercialized PCL-based 3D-printed biodegradable implants for tissue regeneration.

Figure 8. BellaSeno PCL scaffold products

2.3 Biodegradable Fillers that Stimulate Facial Tissue Regeneration

Third-generation facial fillers utilize biodegradable polyester microspheres as core components, enabling a transition from simple filling to in-situ tissue regeneration and repair.

Figure 9. Representative absorbable bio-stimulatory dermal filler products

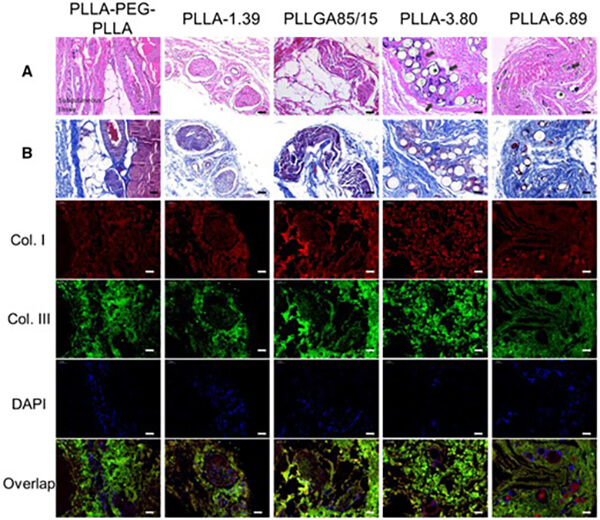

Researchers prepared PLLA and PLGA microspheres and injected them into the dorsal skin of rabbits. In vivo studies showed that microsphere degradation rate strongly correlates with foreign-body reactions and collagen regeneration. Rapidly degrading microspheres induce inflammation and produce shorter-lasting collagen regeneration. PLLA microspheres with appropriate molecular weight and degradation rates strongly stimulate type I and III collagen regeneration, yielding long-lasting cosmetic effects [8].

Figure 10. H&E (A), Masson’s trichrome (B), and immunofluorescence staining of subcutaneous tissue 6 months after injection (scale bar: 50 ╬╝m). Asterisks indicate microspheres (pores), black arrows indicate infiltrated immune cells.

3. Three Core Advantages of Biodegradable Polyesters

3.1 A ŌĆ£Safety CredentialŌĆØ Recognized by the Body

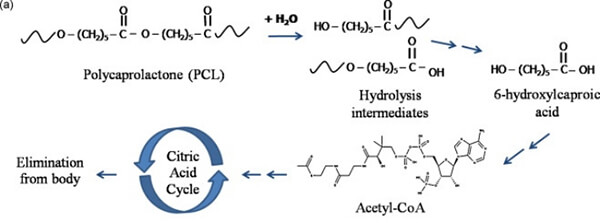

Biodegradable polyesters degrade via hydrolysis and enzymatic cleavage into monomers. PLA degrades to lactic acid, PGA to glycolic acid, and PCL to 6-hydroxyhexanoic acidŌĆöall of which enter normal metabolic pathways and are ultimately oxidized to COŌéé and water.

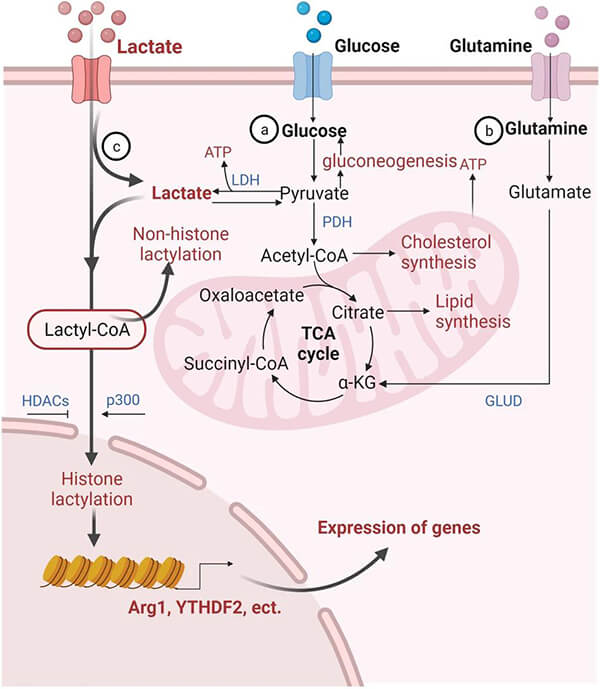

Metabolic pathways:

- PLA ŌåÆ lactic acid ŌåÆ pyruvate ŌåÆ mitochondria ŌåÆ TCA cycle

- PGA ŌåÆ glycolic acid ŌåÆ glyoxylic acid ŌåÆ glycine or oxalate ŌåÆ TCA cycle / renal excretion

- PCL ŌåÆ 6-hydroxyhexanoic acid ŌåÆ acetyl-CoA ŌåÆ TCA cycle

Figure 11. Lactic acid metabolism pathway [9]

Figure 12. PCL metabolism pathway [10]

Therefore, the degradation products of these materials are not toxins requiring elimination, but physiological fuels that the body can ŌĆ£recycle,ŌĆØ avoiding cumulative toxicity and ensuring controllable inflammation and predictable biosafety.

3.2 A Versatile ŌĆ£Material Building BlockŌĆØ

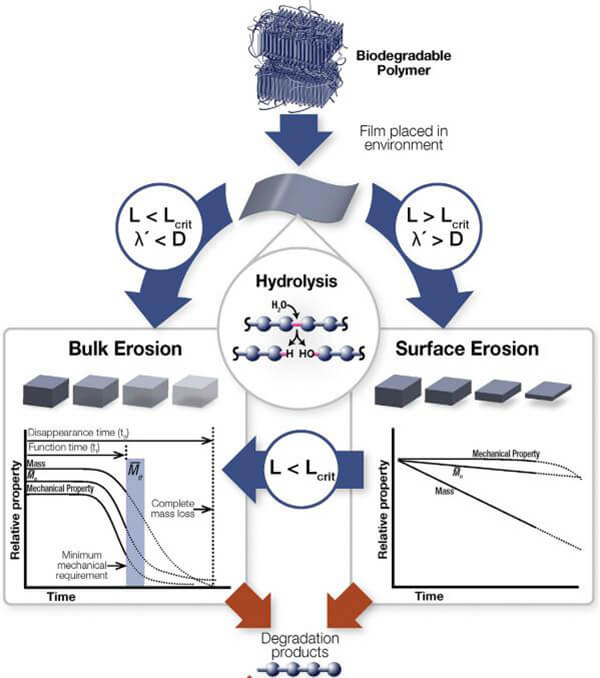

During synthesis and modification of biodegradable polyesters, properties can be controlled across four structural levelsŌĆömonomer, chain structure, aggregated structure, and morphology. By designing monomer composition and ratios, adjusting molecular weight and distribution, modifying end groups, and controlling block, branched, or crosslinked structures, the degradation rate, mechanical properties (strength, toughness, modulus), and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity can be precisely tailored.

3.2.1 Controlling the Degradation Cycle

The key value lies in matching the degradation cycle with the rhythm of tissue regeneration. Materials act as ŌĆ£temporary functional scaffolds,ŌĆØ and their degradation actively modulates the local microenvironment.

Figure 13. Degradation process of biodegradable polymers in vivo [11]

(L: thickness; Lcrit: critical thickness; ╬╗’: hydrolysis rate constant; D: diffusion coefficient)

Monomer structure determines ester bond stability. For example:

PLA has a methyl side group that slows hydrolysis.

PGA has no side group, degrades faster.

Copolymerizing GA with LA accelerates PLA degradation.

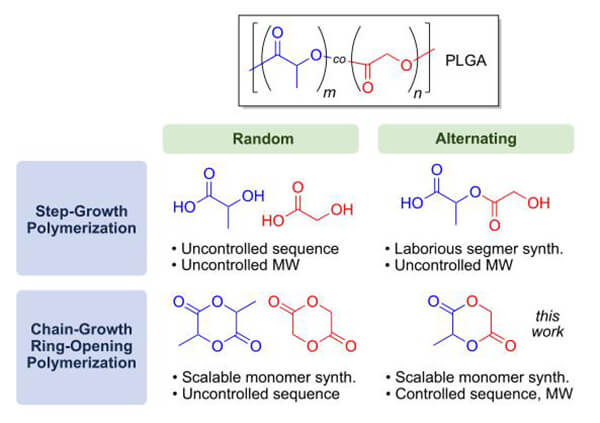

Figure 14. Two synthetic routes for PLGA [12]

Crystallinity is another major factor. High-crystallinity materials degrade slowly; copolymerization reduces crystallinity and accelerates degradation. Increasing porosity and surface area significantly accelerates degradation, while dense films or bulk materials degrade slowly. Introducing crosslinks or branching can restrict chain mobility and slow degradation.

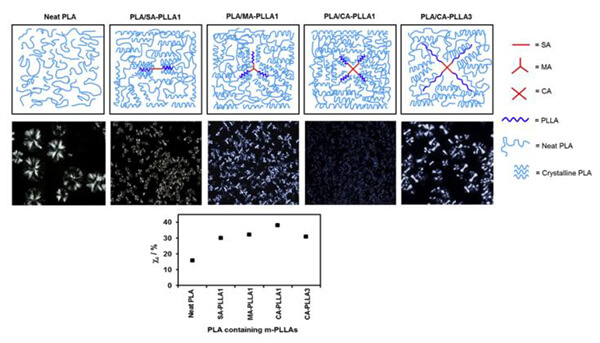

Figure 15. Nucleation mechanisms of different PLA topologies [13]

3.2.2 Tuning Mechanical Properties (Strength, Toughness, Modulus)

Mechanical properties depend on intermolecular interactions and energy dissipation mechanisms. Monomer rigidity determines modulus and strength. For instance, copolymerizing lactide with caprolactone to produce PLCL tunes the mechanical properties of PLLA or PCL. Crystallinity also affects tensile strength, impact resistance, and brittleness. Higher crystallinity generally increases PLA rigidity and strength.

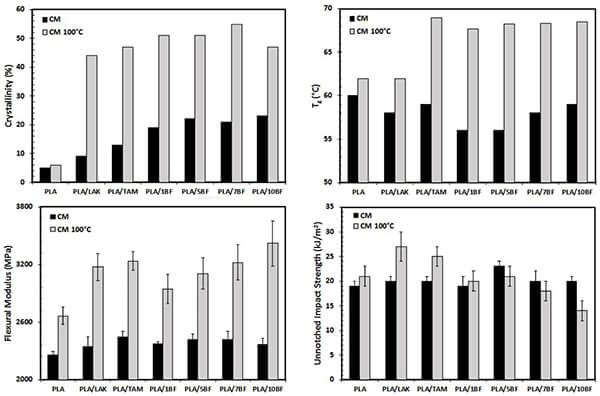

Figure 16. Effects of nucleating agents and annealing on PLA crystallinity, Tg, modulus, and impact strength [14]

3.2.3 Tuning Hydrophilicity/Hydrophobicity

Hydrophilicity is determined by surface chemistry and microstructure, influencing cell adhesion and early-stage degradation. It can be tuned by incorporating hydrophilic segments, adding ionic end groups, increasing surface roughness, or creating microŌĆōnano hybrid structures.

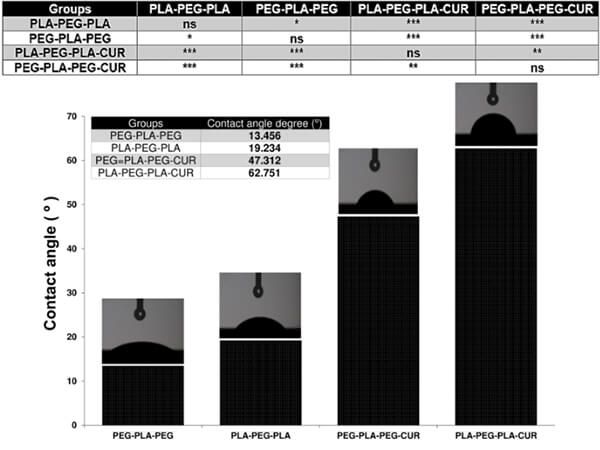

Figure 17. Contact angle measurements of various PEG-PLA copolymers [15]

These four structural levels are interdependent. For example:

Adding flexible segments increases toughness but reduces crystallinity and accelerates degradation.

Incorporating PEG improves hydrophilicity but reduces mechanical strength and increases degradation rate.

Thus, successful material design requires deep understanding of structureŌĆōproperty relationships and identifying optimal balances for specific applications.

3.3 A ŌĆ£Manufacturing PartnerŌĆØ Compatible with Multiple Processes

The thermoplasticity of biodegradable polyesters makes them suitable for diverse manufacturing technologies.

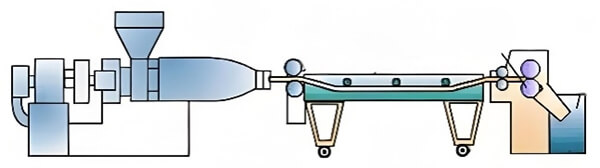

Screw extrusion heats, shears, and melts polymer pellets or powders, extruding them into continuous filaments, tubes, and sheetsŌĆöused for biodegradable sutures and stent substrates.

Figure 18. Screw extrusion diagram

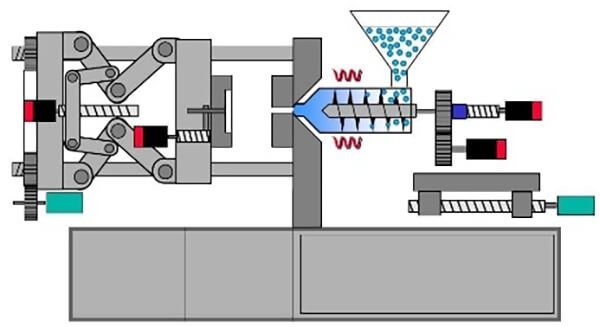

Injection molding heats and plasticizes polymers, then injects them under high pressure into a closed mold, producing complex 3D components with high dimensional accuracyŌĆösuch as biodegradable bone screws and plates.

Figure 19. Injection molding diagram

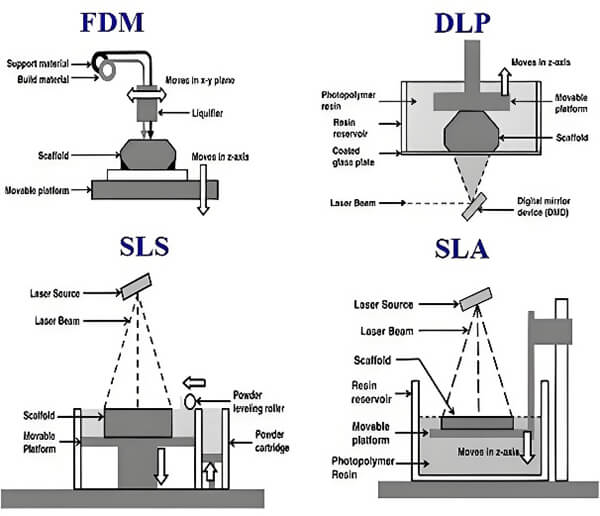

3D printing enables personalized manufacturing of complex structures for customized implants and is central to tissue engineering.

Figure 20. 3D printing technology diagram

Figure 21. Polymer scaffolds for bone regeneration produced by three common printing systems [16]

(FDM: PCL/PLGA, PEEK, PLA;

SLS: PCL/TCP, PCL, PCL/TCP;

SLA: PDLLA-PEG-PDLLA, PDLLA, PCL.)

The expanding applications of biodegradable polyesters signify a shift in medical devicesŌĆöfrom ŌĆ£passive implantationŌĆØ to ŌĆ£active regeneration.ŌĆØ These materials represent not just technological progress, but a patient-centered clinical philosophy: more precise interventions, more natural recovery, and greater peace of mind. We firmly believe that material innovation is the fundamental driving force behind medical advancement. As pioneers and practitioners in biodegradable materials, eSUNMed is committed to partnering with global medical device innovators to unlock more possibilities for human health.

Figure 22. eSUNMed provides diversified custom processing services for biodegradable polyester materials

References

[1] Zong J, He Q, Liu Y, Qiu M, Wu J, Hu B. Advances in the development of biodegradable coronary stents: A translational perspective. Mater Today Bio. 2022 Jul 19;16:100368.

[2] Alonzo M, Primo FA, Kumar SA, Mudloff JA, Dominguez E, Fregoso G, Ortiz N, Weiss WM, Joddar B. Bone tissue engineering techniques, advances and scaffolds for treatment of bone defects. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2021 Mar;17:100248.

[3] Zhou H, Ge J, Bai Y, Liang C, Yang L. Translation of bone wax and its substitutes: ┬ĀHistory, clinical status and future directions. J Orthop Translat. 2019 Apr 11;17:64-72.

[4] Yan F, Lv M, Zhang T, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Liu Z, Wei R, Cai L. Copper-Loaded Biodegradable Bone Wax with Antibacterial and Angiogenic Properties in Early Bone Repair. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2021 Feb 8;7’╝ł2’╝ē:663-671.

[5] Juncan, Anca MariaŃĆüMois─ā, Dana GeorgianaŃĆüSantini, AntonelloŃĆüMorgovan, ClaudiuŃĆüRus, Luca-LiviuŃĆüVonica-╚Üincu, Andreea LoredanaŃĆüLoghin, Felicia,Advantages of Hyaluronic Acid and Its Combination with Other Bioactive Ingredients in Cosmeceuticals,Molecules ’╝łBasel, Switzerland’╝ē, 2021-07, Vol.26 ’╝ł15’╝ē, p.4429.

[6] Tham T, Roberts K, Shanahan J, Burban J, Costantino P. Analysis of bone healing with a novel bone wax substitute compared with bone wax in a porcine bone defect model. Future Sci OA. 2018 Jul 26;4’╝ł8’╝ē:FSO326.

[7] Alonzo M, Primo FA, Kumar SA, Mudloff JA, Dominguez E, Fregoso G, Ortiz N, Weiss WM, Joddar B. Bone tissue engineering techniques, advances and scaffolds for treatment of bone defects. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2021 Mar;17:100248.

[8] Zhang Y, Liang H, Luo Q, Chen J, Zhao N, Gao W, Pu Y, He B, Xie J. In vivo inducing collagen regeneration of biodegradable polymer microspheres. Regen Biomater. 2021 Jul 15;8’╝ł5’╝ē:rbab042.

[9] Li, X., Yang, Y., Zhang, B. et al. Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther 7, 305 ’╝ł2022’╝ē.

[10] Maria Ann Woodruff, Dietmar Werner Hutmacher,The return of a forgotten polymerŌĆöPolycaprolactone in the 21st century,Progress in Polymer Science,Volume 35, Issue 10,2010,Pages 1217-1256,ISSN 0079-6700.

[11] Bronwyn Laycock, Melissa Nikoli─ć, John M. Colwell, Emilie Gauthier, Peter Halley, Steven Bottle, Graeme George,Lifetime prediction of biodegradable polymers,Progress in Polymer Science,Volume 71,2017,Pages 144-189,ISSN 0079-6700.

[12] Yiye Lu, Jordan H. Swisher, Tara Y. Meyer, and Geoffrey W. Coates’╝īChirality-Directed Regioselectivity: An Approach for the Synthesis of Alternating Poly’╝łLactic-co-Glycolic Acid, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 4119ŌłÆ4124 .

[13] Yupin Phuphuak, Suwabun Chirachanchai,Simple preparation of multi-branched poly’╝ł L -lactic acid’╝ēand its role as nucleating agent for poly’╝łlactic acid’╝ē’╝īPolymer .2013,54’╝ł2’╝ē:572ŌĆō582.

[14] Heather Simmons, Praphulla Tiwary, James E. Colwell, Marianna Kontopoulou,Improvements in the crystallinity and mechanical properties of PLA by nucleation and annealing,Polymer Degradation and Stability,Volume 166,2019,Pages 248-257,

[15] Neda Rostami,Farzaneh Faridghiasi et al.Design, Synthesis, and Comparison of PLA-PEG-PLA and PEG-PLA-PEG Copolymers for Curcumin Delivery to Cancer Cells,Polymers 2023, 15’╝ł14’╝ē, 3133.

[16] Chen Y, Li W, Zhang C, Wu Z, Liu J. Recent Developments of Biomaterials for Additive Manufacturing of Bone Scaffolds. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020 Dec;9’╝ł23’╝ē:e2000724.